Sponsored by: Peter Gabany, Limelight Advertising & Design

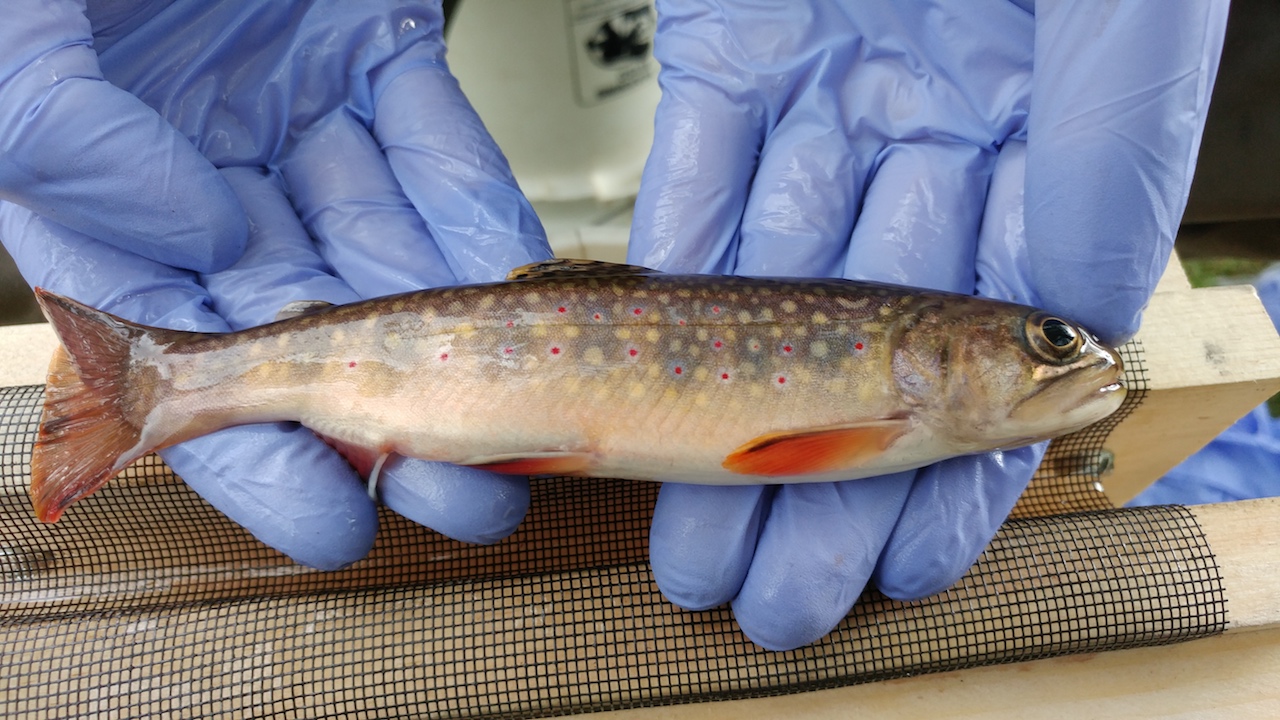

Trout Stats: Brook is 160 mm (6.3 inches) in length and currently weighs in at 42.6 grams (1.5 ounces)

In 1972 – a long time ago my grandfather entrusted me with a then, vintage cane fly rod. This launched a fascination with fishing and in the Eastern Townships of Quebec little did I know that I would be fishing for “specs” (speckled or brook trout).

Since that time, we have had the pleasure of fishing all across the country for lake trout, grayling, cut throat, rainbows, browns and salmon. Sitting at a tying bench in the dead of winter, reminiscing with friends while tying flies, the conversation always migrates to our love of ‘brookies’.

What name would be more natural than BROOK. In our business–design and marketing, the metaphor of fly fishing is echoed each day. You must read the water, look to the bottom of the stream to see what insects are prevalent and consider the fish–to see what they are eating. Only then can you design the fly that simulates the natural and angle in such a way as to present that fly so as to attract the fish you desire.

In our experience as anglers of business, brook trout are motivated customers. Where you have to drop a fly a couple of feet in front of a rainbow or brown, a presentation of that same fly in one section of the stream will call the attentions of a brook trout 10 feet away. The frenzy in which they hit your fly is electrifying. A brookie will leap from the security of it’s water blanket and engulf its prey. The ensuing fight–regardless of size–is possibly the most rewarding of taking any other sort of fresh water species. And landing a “natural” spec all the more gratifying.

A quick release from a barbless fish, restores the stream with sustainable population–that our friends and children may fish another day.

Learning that a young 14-year old, Jacob Bowman, started a school project and nurtured it whence Scott Blair and the research team embraced and formalized the study, further attracted our interest to participate.

Initiatives taken by our youth deserve that nurturing and support. Already the word of this study has drawn many eyes and it is our hope that BROOK’s journey will tell a tale and lead to greater understanding, conservation and preservation of these beautiful and mighty gifts.

Trout Trivia: Brook trout love it when flies ‘drop-in’ for dinner!

While fly-fishing may not be possible in small headwater streams like Harper Creek, it seems that anglers practicing this art have the right idea.

The field of bioenergetics – modelling how calories are transferred up the food chain – is demonstrating that brook trout are far more dependent on terrestrial insects (land bugs), that fly or fall into the creek, than was previously thought. In fact, a recent study by Sweka & Hartman (2008) discovered that as high as 51 to 63% of a trout’s annual energy can be derived from a diet of land dwelling bugs such as beetles, aphids, moths and butterflies.

Looking at patterns on a seasonal basis, Utz & Hartman (2007) found that brook trout in the Appalachian headwater streams they were studying consumed more terrestrial invertebrates (animals without a spine) in spring and summer, while winter months saw a greater reliance on bigger vertebrate (animals with a spine) prey such as crayfish, frogs, salamanders and fish. In streams where vertebrates are not plentiful, caddisflies, order Trichoptera, were found to be a winter staple.

A truly interesting result of recent bioenergetics modelling is the discovery that brook trout would have to eat up to 130% more aquatic invertebrates to compensate for a loss of terrestrial invertebrates from their diet! Why is this relevant?

Well, if we know that food more than any other factor, including temperature, is the limiting factor for brook trout growth, then protecting that source of food protects the trout (Sweka & Hartman, 2008). Assuming that studies completed in Appalachian streams also apply to brook trout populations in Southern Ontario, then what can we do to ensure that terrestrial insects remain available for fish growth, survival and reproduction?

One of the easiest management steps would be to ensure that a healthy riparian zone (the area of vegetation that separates the creek from adjacent land uses) is left in place along creek banks. Sweka & Hartman (2008) also suggest leaving overhanging branches that allow non-flying insects to fall into streams.

Healthy native riparian vegetation also protects creeks from stream bank erosion, shades them, and filters sediments that are carried downslope by snow melt and stormwater runoff. Reducing the sediment load in a stream benefits brook trout because they are ‘sight’ feeders, finding their prey visually rather than sensing them by smell, heat, vibration or other sensory mechanisms. Research by Sweka & Hartman (2001) found that as the turbidity of water increased, becoming less clear, brook trout growth decreased. While some of the change in growth rate could be attributed to the inability to see prey, researchers also discovered that impacted brook trout had to change their feeding strategies, and begin actively foraging rather than waiting for prey to drift by. From an energetics perspective, this extra swimming comes at a cost as more calories are burned when the trout are forced to hunt due to cloudy water (Sweka & Hartman, 2001).

Fortunately for Brook, the Brook Trout, there are many opportunities to increase the riparian zone on both municipally, and privately-owned lands along Harper Creek. Riparian restoration would have a significant, positive impact on the trout, particularly those inhabiting the main stem of Harper Creek where erosion and stormwater runoff create challenges to brook trout survival.

For more information on Brook Trout prey preferences, the following referenced publications are very helpful:

Sweka J.A. and K. J. Hartman. 2001. Effects of turbidity on prey consumption and growth in brook trout and implications for bioenergetics modeling. Can. J. Fish. Aqua. Sci. 58: 386-393.

Sweka, J.A. and K. J. Hartman. 2008. Contribution of Terrestrial Invertebrates to Yearly Brook Trout Prey Consumption and Growth. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 137:224-235.

Utz, R.M. and K.J. Hartman. 2007. Identification of critical prey items to Appalachian brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) with emphasis on terrestrial organisms. Hydrobiologia. 575:259-270.